They worship the Sun: the only god as cruel as they are.

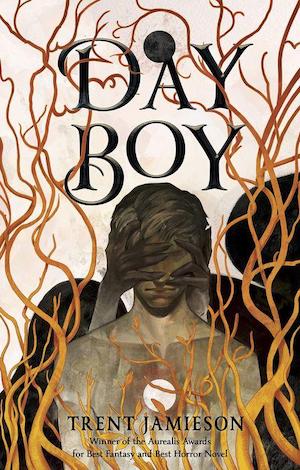

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Day Boy by Trent Jamieson, out from Erewhon Books on August 23rd.

They worship the Sun: the only god as cruel as they are.

The Masters, dreadful and severe, rule the Red City and the lands far beyond it. By night, they politic and feast, drinking from townsfolk resigned to their fates. By day, the Masters must rely on their human servants, their Day Boys, to fulfill their every need and carry out their will.

Mark is a Day Boy, practically raised by his Master, Dain. It’s grueling, often dangerous work, but Mark neither knows nor wants any other life. And, if a Day Boy proves himself worthy, the nightmarish, all-seeing Council of Teeth may choose to offer him a rare gift: the opportunity to forsake his humanity for monstrous power and near-immortality, like the Masters transformed before him.

But in the crackling heat of the Red City, widespread discontent among his fellow humans threatens to fracture Mark’s allegiances. As manhood draws near, so too does the end of Mark’s tenure as a Day Boy, and he cannot stay suspended between the worlds of man and Master for much longer.

Thom looks at me, up from the thing he’s whittling. A stake—taipan curled around it. He puts his carving down, keeps a hand knuckled around the knife, and listens. Singing. Wind’s howling, so it could be that. Shouldn’t be able to hear much of nothing anyway; we had a snowfall about a week back, last huff of winter as spring starts to spring. But there’s that windblown song, carried to us from the edge of town. Persistent and sweet.

“It’s the cold children,” I say.

Buy the Book

Day Boy

His face does a little sort of skip, his eyes widen a bit. “You’re lying. No cold children around here.”

“No, not often. But they come. There’s cold children everywhere.” I tap my chest. “We’ve a truce and everything.”

“You got a truce with them?”

I consider. “More of an agreement.”

The singing’s getting louder. It grabs you by the short hairs, faint then loud, then faint again. It gets in your blood, and plays with the rhythm of your heart.

“How’d you sleep with them singing like that?”

“Best to ignore it,” I say.

“Where’s Dain?”

“Out on business, they all are. Said he might be gone all night.”

Which is why, I reckon, they’ve chosen to come here now.

The Masters are away. It’s a time for children. “Best we stay indoors,” I say.

I grab my coat.

Thom’s still holding his knife, a little thing scarcely good for grazing anything but soft supple wood. And the cold children are hard. “I’m not going out there.”

“Suit yourself,” I say. I don’t blame him; last time I took him into the night, he saw the truth of our Masters, plain and simple. This isn’t much safer; might be the opposite.

But he comes when I open the door. Scarf around his neck, shrugging into his coat.

Dougie’s walking down our street, whistling.

“You gonna see the cold children,” I say.

He smiles, gives an expansive sort of wave. “Got an agreement, don’t we?” His eyes are shining. I reckon mine are, too.

So it’s the three of us that walk along the cold dirt road heading out of town. Why just us, not Grove or the others? I couldn’t tell you. And the singing gets louder and quieter, and louder, but gradually the quieter is shorter and the louder longer.

Past the end of town near the bridge, there’s a clearing edged to the west with trees. Old ones, pines as high as anything out of the City beneath the Mountain. We stand there, and the singing swells and fills our blood.

I don’t know the words, but there’s hunger in them, and something of the stars and the darkness between. There’s a weariness, too. I feel all weepy just standing there, and I catch Dougie rubbing at his eyes with a handkerchief, and I wonder why I didn’t bring one; my nose is streaming in the cold. And a wind’s got up, so loud and fierce it almost drowns out the singing, until it gives way.

And then, in the dark, the singing stops. And it’s silent.

Thom grabs my hand.

“No need fer that,” I say, then I realise that it isn’t Thom. The fingers have snatched the heat from me, my teeth are chattering. A girl with bright eyes, moon-bright, dead-light-bright, looks up at me and smiles.

Her teeth are sharp as killing blades, her smile is cold and cutting, and about as beautiful and dangerous a thing as you might see.

“Hello, Mark,” she says, all sing-song and radiance.

“Mol,” I say.

“You remember me?” Mol asks.

Of course I do. I remember when she wasn’t so cold. When she used to pull my hair, when I was younger than her. But now she’s younger than me and more ancient—there’s the timeless weight of star-shine to her.

I blink. “I remember our agreement.”

“Agreements are odd things, Mark. Tenuous. Light as the wind, and as swift to shifting.”

I clear my throat. “We’re bound to them, by Law.”

“No lawyers in the woods. Just trees and the air and us.”

And there, in the woods, I feel my throat catch. She’s got that sharpest of grins out, the widest of eyes.

“Where’s Thom?”

“Safe.”

“Safe? Master would kill me if I—”

“Dain is far away, far, far away. And I am here.” She touches my throat with a fingertip. Mol’s eyes are bright as glass beads.

“Yes, you are.”

“Yes, I am. Shall I sing for you?”

“I think you already have,” I say.

“Shall I sing some more?”

I nod.

And she does, and I remember those days before she was cold. I remember the sadness of it, the death that wasn’t a death, but a mistake, a bit of the Change that got in her and spread. Masters have a dread of ending those they make—unless they’re born of punishment, like those insurgents marked for a cruel death beneath the Sun. Such mistakes are hard admitted, and feared, too, feared almost as much as anything.

Most of the cold children do die in time, of their own accord. But those that don’t, they call to each other. Like lonely birds or wolves or something mournful and beautiful. And they gather, and they sing.

Sometimes they hunt.

But we have an agreement.

She’s singing, they’re all singing, her kindred gathering around, glowing all fairy-like, dancing, too. And it’s a sound sweet as it is terrifying. It’s a hook that can land you, lance you so deep.

She touches me once and hesitates. “Your agreement is sound, my sweet little boy. But we can still play.”

I blink and there’s Thom, and there’s Dougie. And they’re looking at me eyes so wide it’d be funny if we weren’t piss-ourselves scared.

“Run,” a little voice whispers.

“Run,” I say. And the others are already running, and things are coming out of the dark: all teeth and claw and leering grin. And that forest seems awful big, all at once, and we’re awful small and racing. Snot and tears frozen to our faces, lungs as raw as the winter-hard earth. Trees slapping us, branches snapping and grabbing. Wind a screaming pressure at our backs, only to flip—light as the wind and as swift to turning—and whip our faces like we’re the ones running in circles, and maybe we are, to that sound of children that aren’t children singing.

We run, and we run.

I don’t know when I fall, but I do, and something grabs me, and lifts me as though I’m feather light, and I struggle. Like a tiny bird might struggle in the hands of a giant. Cold hands. Hands colder than you could imagine grip me.

“My, you’re all grown up, aren’t you?”

And she laughs, and it’s the sweetest, most terrible sound.

I wake in my bed, my chin bloody, my body a length of bruise given arms and legs and a voice to squeak. Out of the sheets I jump, and they’re tight around me. I struggle free. There’s a boot still on one foot, and muddy footprints leading to my bed. The room’s cold, the window’s open, and first light is shining through.

I check on Thom. He’s all right, too. Sleeping, thumb in his mouth. Doesn’t even stir, but he’s breathing. There’s specks of blood on his pillow. I know we lost a little blood. But that’s all right.

I’ve half-convinced myself it’s a dream when I go downstairs. Dain’s left me a note.

You should know better than to play with children, it says.

Excerpted from Day Boy, copyright © 2022 by Trent Jamieson.